Li S, Peng Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Yan X, Zhang L, Liu J, Zhao L, Liu J, Qian J, Zhai N, Dong L, Ruan J, Zhang P, Wei X, Liu Y, Ma Q, Huang W, Zhang Q, An C, Liu J, Sheng L, Zhang H, Li J; ESPRIT Investigators. Effects of Intensive Blood Pressure Control in Patients With Frailty: A Post Hoc Analysis From ESPRIT. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025 Oct 15:S0735-1097(25)07783-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2025.08.092. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41091084.

When I see an 80-something man or woman in the hospital, particularly if they’ve come in for a fall or a severe electrolyte abnormality, a frequent question I will pose to the residents is, “Will he/she live longer or feel better because they take this blood pressure medication?”

The answer is usually an obvious “no.”

Yet, given the current level of allegiance to intensive blood pressure control, there has been a recent effort to see just how far into life this paradigm can be stretched. A recent study in The Journal of the American College of Cardiology (https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2025.08.092) suggests that the answer is all the way to the end.

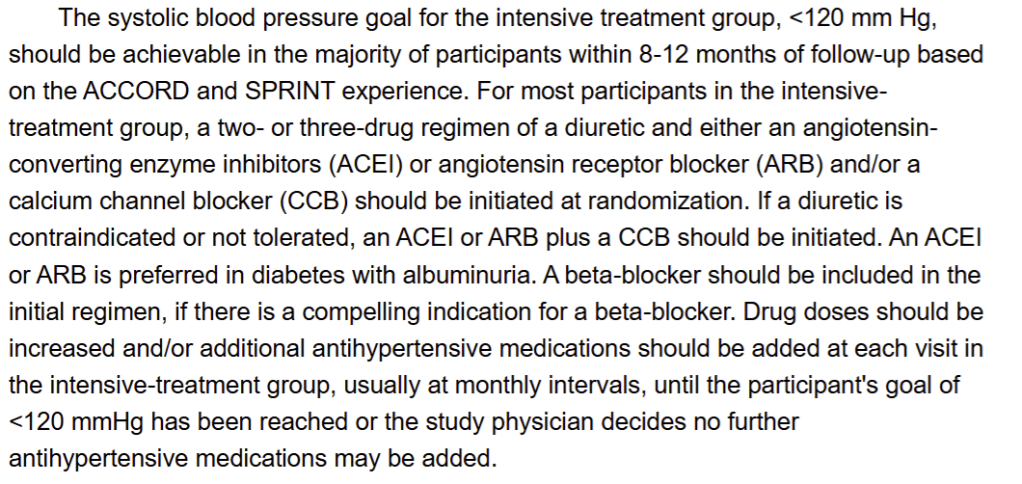

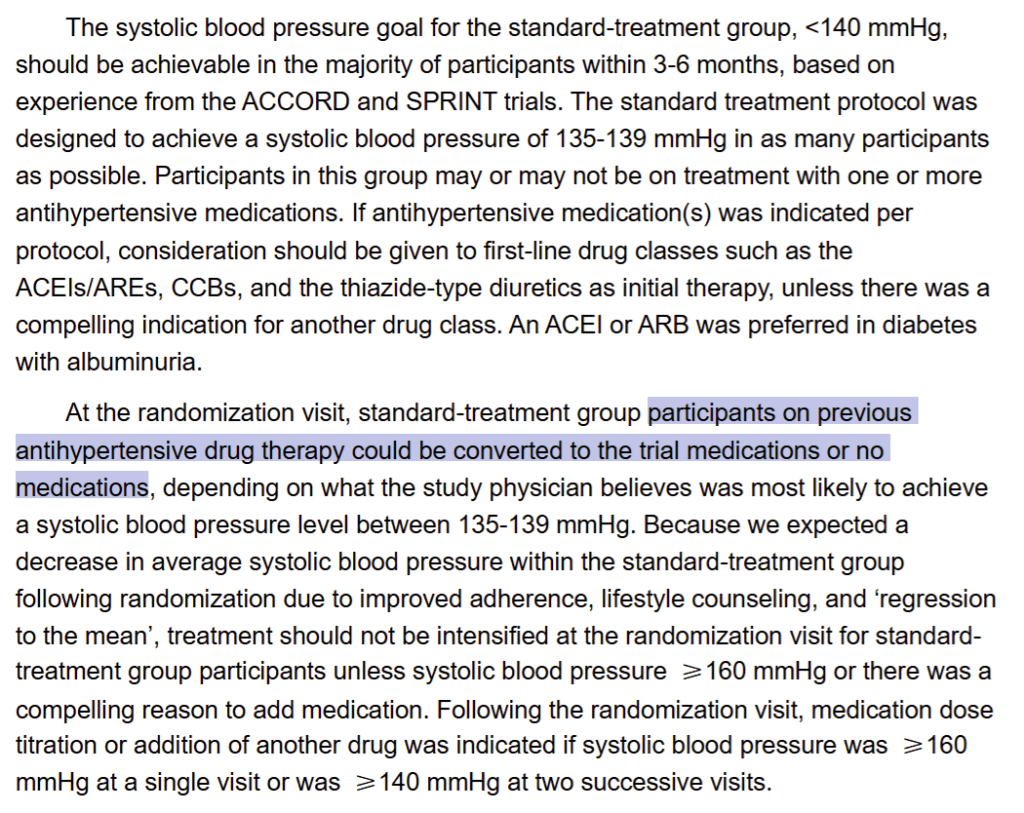

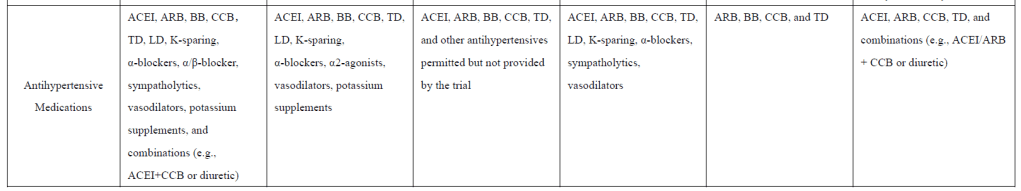

This post-hoc analysis of the ESPRIT study looked at more than 11,000 patients across a stratified frailty index and showed no difference in impact of intensive treatment on major adverse cardiovascular events or safety according to frailty. However, as always, there is no information about what medications anyone was given, which is obviously a fundamental factor in understanding efficacy and safety of treatment.

What is reported, however, is that more frail patients reached goal blood pressures more slowly, if at all. It seems that while demonstrating the safety of intensive blood pressure control, physicians (very reasonably) treated more frail patients more cautiously, potentially reducing their risk, but also undermining the premise of the study. While trying to determine whether intensive blood pressure control was safe and effective for everyone, they intuitively knew that there was increased risk in more frail patients.

In fact, the authors conclude that “cautious titration of antihypertensive therapy and close monitoring of kidney function” is needed. So is it safe for everyone? If so, why do we need to be more cautious in certain patients?

As an aside, in the adverse events table, the numbers for the severe events of interest (hypotension, syncope, electrolyte abnormalities, injurious falls, acute kidney injury) out of sub-cohorts of between 800 and 2600 patients are surprisingly low, with incidences in the single digits. These numbers seem highly unlikely, particularly in this population, raising questions about the reporting and thus the overall conclusions.

For the good of our frail and elderly patients, hopefully these results do not replace common sense.